How I started talking science

Published:

This Thursday, I approached the stage of the Cambridge Union’s debating chamber with a plastic bag in my hands. Inside, I’d placed a can of tomato soup and a bottle each of sriracha, dishwashing liquid, and fruit juice. And no, I wasn’t using them to share a recipe for a haphazard dinner …

I’d brought them to tell a story a decade in the making — the story of fifty thousand people who saved ten times as many lives.

Trying scary things

It was December 2023, and I had reached a tedious stage of my doctorate. I was extracting data and coding to make sense of the published literature on my topic, which I wasn’t sure I could even define. Then, in some newsletter or mass email or tweet, I spotted a sparkly opportunity: the chance to take part in the world’s biggest science communication competition, Famelab.

I love communicating. I’ve always enjoyed writing and visual forms of expression, and in the last few years, I’ve become immersed in music performance and data visualisation too. But I could never speak. Sure, I could hold my own in a conversation with friends, but in the presence of authority figures, my mind would go blank — or I would ramble on at a mile a minute, never quite confident in what I wanted to say. Luckily, the latter improved a little after I finished university as I began to engage regularly with communities who demand a more reasonable pace. Still, speaking to a room of staring strangers was very far from where I wanted to be.

Nevertheless, I soon learned that this type of communication, the kind often required in public engagement, is highly prized in academia. Experience making complex science clear, and even exciting, could make a grant application shine. Besides, I had already convinced myself to try scary things during this first PhD year, and I thought that I could survive even the worst humiliation this opportunity could offer. So I took my chance.

First round

After signing up to participate in Famelab, the organisers convened an online training session to introduce us to the fundamentals of science communication. I joined during my lunch break, but had to leave halfway through. Luckily, I had access to a wealth of resources from previous contestants and professionals in the field. And YouTube never let me down!

Soon, it was crunch time. Our first entry into this year’s competition came in February, when we were asked to submit a recording of us speaking about any scientific topic for three minutes or less without any slides. These “heats” were contested by researchers from all across the East of England, including some parts of London (I was confused too). Because I had been reading about our research group’s previous work for the last few months, I decided to talk about one of our studies: the INTERVAL trial. I told the story of Ava, an imaginary young woman studying architecture at university who procrastinated on her essays by bingeing k-dramas. Ava also had sickle cell disease, meaning that she needed blood transfusions every few weeks to stay alive. Citing the need for volunteers to give blood until we find a synthetic alternative for people like Ava, I introduced the trial, which tested whether increasing the frequency of donations would benefit national blood supplies and steward donor health. I shared the results, which were uncertain, but hopeful: people who give blood more often can save more lives and are at no greater risk of serious complications, but they had lower iron levels and reported feeling a little more faint and breathless too. Over two years, our 45,000 participants may have saved more than 60,000 lives with their donations.

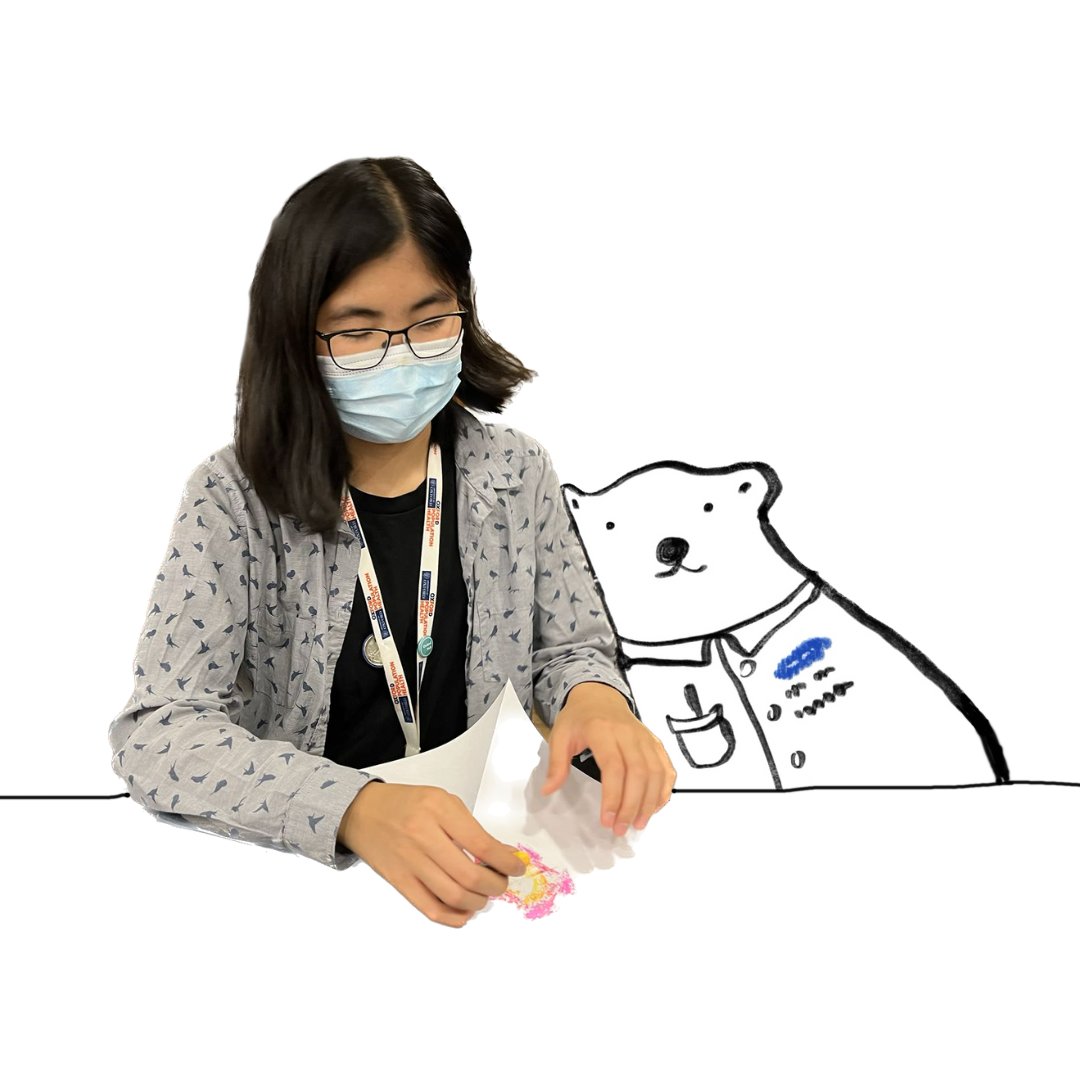

Here I am explaining that the human body regenerates blood in a few weeks, almost like a lizard can grow back its tail (but not really like that).

After what felt like hundreds of takes one evening, I sent off the video. I found it fun to craft my story, but to my surprise, I enjoyed sharing it with my phone camera too (no heckling received). You know as well as I do, though, that speaking to a live audience is a new challenge altogether …

It takes a village

Within two weeks of submitting my entry, I was notified that I was fortunate enough to progress in the competition. Of course, I had enough hope to try out, but I never expected to make it through. With our in-person regional final taking place in the next month, I needed to start preparing in earnest.

First, I had to write a new talk. We were allowed to speak on the same topic, but had to change our angle. After a few bullet-point brainstorming sessions, I settled on an explainer of an enormous challenge in my field: what we call the “healthy donor bias”. This is the idea that it’s hard to determine the effect of blood donation on individuals’ health because people who self-select to give blood are already very healthy. I knew this might be an obvious concept, so I had to work even harder to stimulate the audience’s excitement.

Once I completed my first draft of my script, I had a few run-throughs with my mirror and stuffed animals. This didn’t give me enough confidence, though, that I could present in front of a “real” audience (no offense to the zoo that I live in). I decided, then, to reach out to others.

Within a day of my call-out on social media inviting friends to chat about my research, some truly wonderful people had booked slots for Teams meetings. It was hard to believe that they were willing to speak with me after a whole day of work or study … I know I would’ve zonked out.

I won’t name those I shared my talk with for their privacy. But among them were researchers, lab scientists, and teachers, all showing me abundant grace as I tried to stall the actual presentation by asking about what they’d been doing that day. And after they heard me speak, they were unafraid to share their feedback. I am eternally grateful for their help — without those practice sessions, I might not have gained the confidence to speak in person at all.

All the while, I continued to make constant tweaks to my talk, thinking about where to use props and refer to real or imaginary people. My poor neighbours must have heard my rambling at the most inopportune times of the day and night …

Soon, the trees were flaunting the change in seasons, and it was the week of the regional final. If you can believe it, I still wasn’t set on my script. I bothered my neighbours again in those few days by asking three of them to listen to my presentation in our kitchen. I set my fruit juice, washing up liquid, sriracha, and tomato soup on the floor and spoke. Though some of them struggled to make it through the talk without giggling (completely unrelated to the seriousness of my topic, I was assured), I received even more helpful feedback, especially about my pace. And I became more confident still.

The final was set to take place on Thursday, March 28th, at 8 pm. On Wednesday afternoon, I was STILL tweaking my script. I had booked a meeting with colleagues kind enough to listen to my talk at short notice, and I came into the office with my dishwashing liquid specifically for the occasion (everything else was too heavy). After I presented, they gave me sage advice about eye contact and audience connection. That was when I drastically changed my plan, moving from speaking in the third person to referring to myself. When preparing for both talks, I had always shied away from saying that word, “I” — it might have felt too vulnerable, or even selfish. But when my colleagues echoed others’ pointers about the power of sharing personal stories, I decided to listen. That meant that I had less than a day to rehearse a talk that had just flipped on its head.

Thursday was a blur. I went into the city centre to work on my research, but could hardly keep still, roving back and forth to our college library’s water dispenser between every sentence I wrote. I resigned myself to doing a little less than usual that day, knowing that there was no use trying to battle with my nerves. I guzzled some noodle soup half an hour before I was expected at our venue, managing to not get a single drop on myself …

Still intact

The Cambridge Union is an unsuspecting structure from the outside, resembling a doctor’s surgery with its block-letter sign and blue-gray reception area. There, us ten finalists gathered in a room close to the debating chamber to receive warmly shouted instructions from Dr Claudia Antolini, a member of the university’s Public Engagement team. She shared that ten years ago, she had stood on a similar stage in Italy as a contestant in their Famelab national final. It was moving to see her delight in supporting us today.

My fellow contestants were scientists from all the disciplines you could think of; physics, marine biology, astronomy, neuroscience, and even artificial reality were represented. I was a little intimidated by how smart they all looked (in both the dress and the brain sense). But I was lucky enough to recognise some of them from our earlier online training, and we soon settled into our own conversations.

At a quarter to eight o’clock, Claudia led us in some bodily relaxation exercises. I’d seen these before — in my four or five years as a theatre musician, I’d stood behind the director or choreographer as they guided a group of actors and singers in preparing for shows every night by moving around and making weird noises with their faces. I’d always do the exercises along with the performers — if I was going to be seated in an orchestra pit for two hours, I probably needed some stretching too. But on Thursday, those exercises were made for me. I held onto that privilege for as long as I could.

By then, audience members had begun filtering into the debating chamber, and our compère, Andrew, had delivered a few punchlines.

Before we were ready, it was time to begin.

I was fourth on the list, and there were only three microphones available, so when the second contestant finished speaking, I put hers on. It was a lapel mic, leaving my hands free to make whatever uncoordinated gestures they wished to.

There I was, waiting by the entrance doors with my Tesco bag and my sriracha, soup, dishwashing liquid, and fruit juice. Then, I was on stage.

I didn’t forget my first sentence, but I did forget my second. I moved on with my third anyway, and on I continued. Before I knew it, I had reached the end, and it was time for questions from the judges. We chatted about historical bloodletting practices, the challenges of incomplete data in health research, and why I cared about the topic I spoke about. Then, it was over.

I had done it — I had talked science in a room full of strangers, and I was still intact.

Can you guess what my groceries were for?

I’m not sure if this event was recorded, but I’m happy to share my script on request. And I didn’t win the regional final, but I never expected to. Our winner, a force of nature on that stage, was entirely deserving, and you can look forward to catching him in the national Famelab final at the Cheltenham Science Festival in June! My biggest thanks go out to the friends, colleagues, and family members who supported me during this months-long journey, even when they had no idea what I was doing or why I was doing it. I am grateful, too, for college and PhD friends who made their way to the Union that night in the rain. While I am far from becoming a public speaker, I tried something incredible this week because of your help.