The Big Day

Published:

Today was going to be the Big Day.

It was mid-afternoon, and I’d just come out of a long departmental meeting. I placed my computer back on my desk and took the lift back downstairs, urging it to move faster. With only my lanyard, phone, and notebook, I headed out into the breeze. I navigated the concrete blocks of our biomedical campus, retracing my steps every two minutes (six months has not been enough for me to know the place where I work). Soon, I arrived at an unassuming one-story structure adorned with red signage and waited for my turn. The anticipation was enough to make me tremble …

You may know that I am pursuing a PhD in blood donor health. Six months ago, I arrived at my current institution with three uneventful donations under my belt. When I started to give blood in 2021, I didn’t know any regular donors, but I must have seen an advert somewhere. And I had my fair share of fears, but they were addressed by blood service staff again and again. I even spent the morning of my nineteenth birthday at a London donor centre, marking the earliest date that I was allowed to return for a second donation. I still have the extra chocolate bar I was gifted that day.

I was a rebellious teenager then, signing up without notifying my family. I don’t know what I was thinking. Blood donation is a low-risk activity, but it is nevertheless one that requires informed consent by the donor. My parents expected to have a say in the consent process too. After all, my body was made from theirs.

After my third donation, I told them what I’d done in the year prior. Then, I worked for years to regain their trust. But I wanted to go one step further: convince them that I could give blood again.

I wrote long emails, created multiple PowerPoint slide decks, and engaged in back-and-forths via text. A few months into this PhD, we reached a breakthrough. Though my scientific understanding of the donation process had advanced only marginally, I had gained a broad understanding of the motivations and barriers some communities face in making decisions about donation. I realised that throwing around statistics or stories of strangers’ lives saved probably wouldn’t work. Instead, I decided to speak openly about the assumptions each of us had about who donors were and what donation could mean for bodies and society. I realised, too, that our discussions needed to be informed by previous experiences of donation, which were situated in vastly different contexts on both sides. In the end, we reached a compromise: I could give only infrequently, with a few other conditions that I will keep private for now. Though I know the blood service would prefer more regular contributions from me, I remain eternally grateful for this allowance. Last year, I didn’t think I could ever donate again.

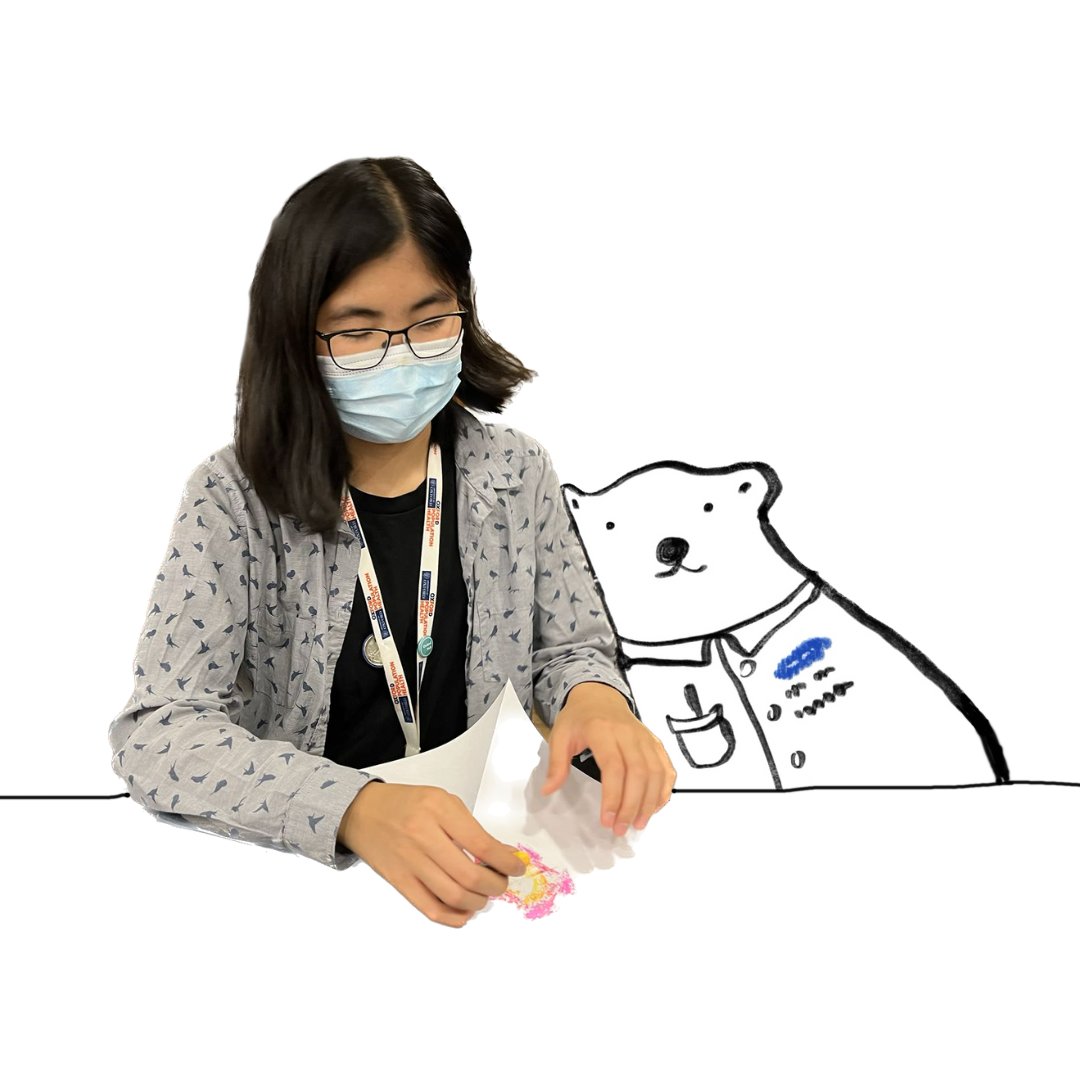

Today is March 19th, what was supposed to be the Big Day. This date marks exactly two years since my third donation, a length of time after which the blood service considers individuals “lapsed donors” (i.e., “this person hasn’t been back for a while … “). In practice, this means that you’re prompted to complete the same questionnaire that’s given to those who had never given blood before. When I returned for my fourth donation, I brought company: three colleagues from my research unit who were kind enough to try something new.

It turned out that my lapsed donor status had begun today. Without boring you with too many details, I passed the screening questionnaire, the health interview, and the haemoglobin test with no issues. When it came time to get acquainted with the donation needle, though, neither of two attending nurses judged my veins to be prominent enough to draw blood from. They said that this could be due to the cold weather or to me not drinking enough water in the hours or days prior. I shouldn’t have been surprised; my vasculature is notoriously fickle. Still, I couldn’t quite believe my ears, and I sat quietly for a few moments while donor centre staff apologised. The agreement I had finally reached with my family seemed distant.

I spent some time alone in the waiting room, scrolling through mundane emails. Then, I chatted with colleagues having biscuits after their successful endeavours. I walked back to the office, getting less lost this time. I had already booked the afternoon off from work, so I was in no rush. A few minutes later, I took a call from a friend, talking about exciting things that demanded my attention in the near future. Though I gazed down at my veins a few times afterwards, that hour didn’t cast a cloud on the rest of the day like I thought it would. I knew that those staff members couldn’t justify collecting blood from me if I couldn’t give a whole unit given the resource waste that it would cause. I did think about whether this outcome was my fault — if I had acted more carefully earlier in the week, could I have donated? In the end, it didn’t matter. Our research teams don’t judge the donors in our datasets by the outcomes of their donations — we know that it’s a privilege to donate in the first place, and that health, motivation, energy, and luck are among many characteristics that need to fall in place for a donation to be successful. I began to recognise that there are some goals that you can never have complete control over, and this was one of them.

I intend to try again when the calendar approaches summer. But even if my veins aren’t deemed suitable to ever give blood again, I can give in other ways, too. I can give my time speaking with diverse publics (just like myself and my community) about donation. I can give my energy to recruiting new donors within my personal network. And I can give my knowledge and skills, those volatile, imperfect, and yet constantly growing things, to building better donation systems for all.

Today is the Big Day — the day I vow to seek my worth in old and newfound places.